From the Colson Center Audience:

“As all Christians know the Bible tells us ‘Do unto others as you would have others do unto you,’ but what are we supposed to do when others are trying to kill us?”

The Colson Center replies:

A lot of the answer would depend on what it is that you’re asking. Specifically, who are the “we” and the “others” in this case? Is this about a personal assault, in the sense of an attempted murder of an individual? Or is it a collective question such as we might face in a time of war? Or, finally, is it a matter of the often-lethal hostility of the world toward the Church?

Each question would garner a different answer, and even then, different Christians would offer different solutions, depending on their theological presuppositions. The overall goal in each case remains the same – seek to live in peace with all men – but the different circumstances would entail different responses.

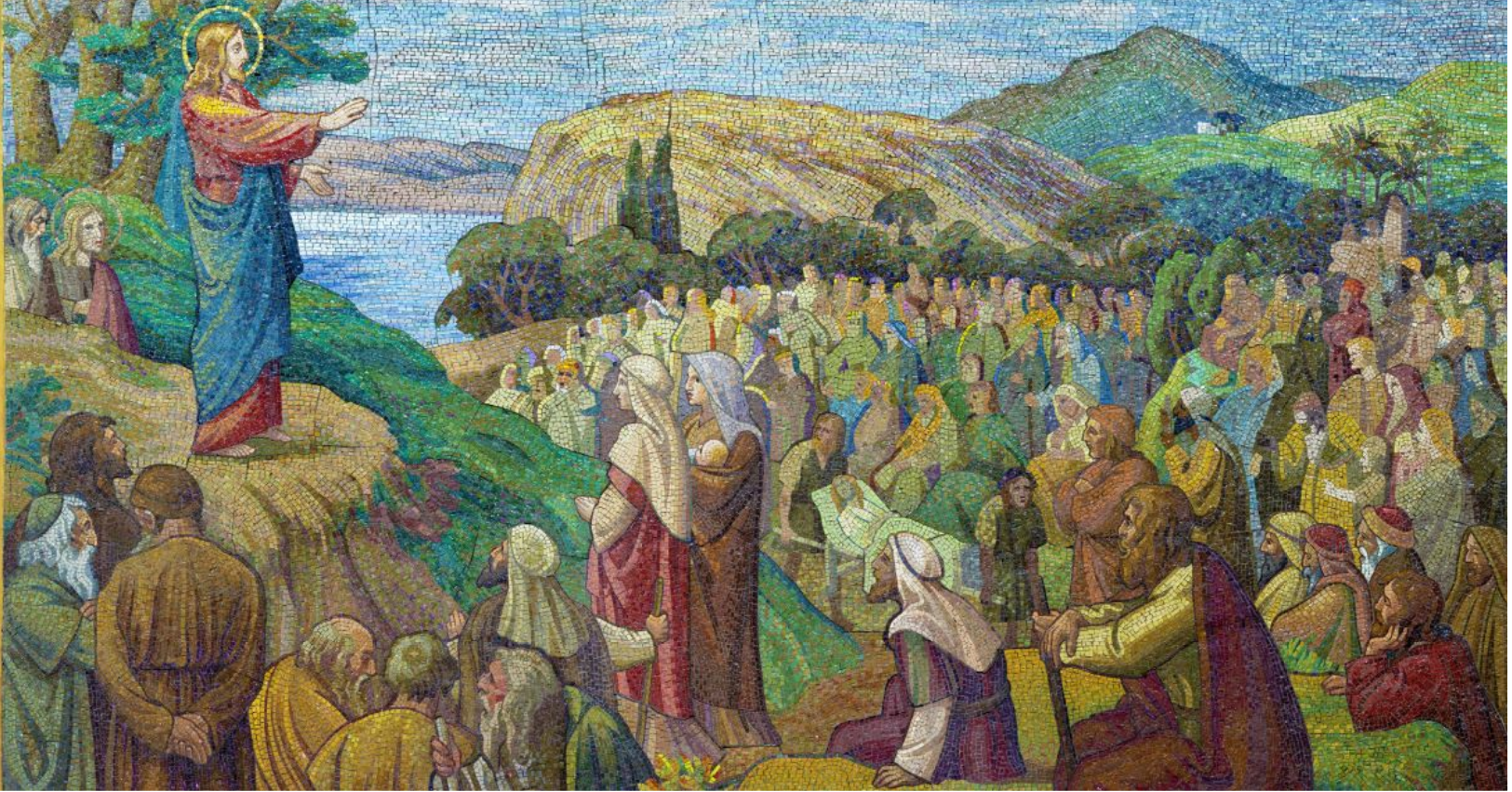

The first of these is what most people mean, and this for good reason. When Christ says, “Do unto others,” it’s pretty easy to see this first and foremost as an individual issue. The word Jesus used there for “you” is plural (like the Southern “y’all”) but since He was speaking to a crowd, this isn’t all that significant. In one sense, it’s the simplest to understand, but, in another sense, it couldn’t be more complicated.

Think about it. If we’re supposed “do unto others,” then what would we have “done unto us” if we were the bad guy? Are we supposed allow them to harm us? That can sound very noble, but what do you say to the abused child? To the kidnap victim? To the rape victim? Very few, even the most ardent pacifists who find no place for forcible self-defense, go so far as to claim absolute passivity in the face of evil. On the other hand, if Christ’s call is to mean anything at all, this can’t be a carte blanche for any sort of retaliation we may consider.

Broadly speaking, the considered opinion of Christian thinkers down through the ages is to see this as rejecting vengeance but allowing self-defense. Yes, there is a strong tradition, including everyone from pacifists in the Early Church and today to the non-pacifist Augustine of Hippo, that has argued that Jesus’ statement in the Sermon on the Mount means that you cannot defend yourself against such an individual attack, though Augustine had room for the defense of others.

However, based on the wider text of the Bible, as well as theological reflection, most commentators have said that Christ did not mean this. Instead, the Christian ought to earnestly seek to avoid a violent confrontation, but not at all costs. If there’s no other way, then it is moral to use force, even lethal force, in self-defense. Now, this self-defense cannot become an act of vengeance or vindictiveness. If someone breaks into my home at night, that is one thing. If I then chase him down in the street or track him to his home, that is another entirely.

If we’re talking about group actions like warfare, then we can appeal to a long history of Christian thought. Again, those like many in the Early Church or those inspired by Anabaptist teaching centuries later see passages like this as their coup de grâce against force. You wouldn’t want to be killed, so don’t kill others. However, the majority of the Church has taken what is known as the Just War position. This is the idea that war is legitimate under certain limited and specified circumstances.

While that list of criteria is long and debated, likely the most widely accepted condition is self-defense. If a nation is attacked, it’s well within its divinely ordained rights to respond in kind. Mind you, as with the case of an individual, it’s vital that the authorities take steps to avoid a fight if possible and not let it devolve into any kind of vindictive overreaction. The goal is to restore the peace broken by another, not to make matters worse or to become like your enemy.

Finally, if we’re talking about persecution of the Church, then neither of these previous examples fits particularly well. There may be a place for citizens of a given country to oppose the violent actions of foreign attack or illegal act by their own government, but this is always on the basis of their humanity, not their Christianity. Yes, our understanding of right and wrong flows out of our Christianity, but the emphasis in the Bible and theology is that persecution for the Faith is to be avoided or endured, never to be opposed in kind.

So, where does that leave us?

There are certain circumstances where a Christian may in good conscience oppose an assault with extreme measures, but two things must be borne in mind. First, when it is right to fight, we must take only those actions that are needed to restore God’s Shalom and never to balance the scales by making the other to feel your pain. Second, and arguably more importantly, while we may fight, it doesn’t follow that we must. Up to the last reasonable option, we must always seek a peaceful solution, even a self-sacrificial solution, to whatever conflicts we find ourselves in. The goal of God is peace in this world, even if, at times, this means using the sword to restore that peace.

Editor’s Note: This is part of an ongoing series where Colson Center staff respond to questions and comments from our audience. If Christianity is true, as we say it is, then Christians should be willing and able to offer what Francis Schaeffer called “honest answers to honest questions.”

You can go here to see more questions like this one.

If there is an issue you would like to see addressed, click on the “Follow Up Question” below.

Posted questions may be edited for form or clarity but not for content.