“Defund the Police!”

It’s been chanted in the streets, written on signs, and plastered on our television screens.

While I am not sold on the solution suggestedd by the chant, I am sensitive to the problem being diagnosed: We’re asking our police to do too much.

As civil society has fragmented, the police are left taking on jobs that used to belong to the whole neighborhood – pastors, grandmothers, concerned citizens and so on.

From conflict resolution in marital disputes, to responding to kids playing outside when they should be school, the police force is being asked to do things that were once the responsibilities of neighbors. If we want to relieve the burden on police, we need to reinvigorate neighborhoods.

From conflict resolution in marital disputes, to responding to kids playing outside when they should be school, the police force is being asked to do things that were once the responsibilities of neighbors. If we want to relieve the burden on police, we need to reinvigorate neighborhoods.

The Need: Healthy Neighborhoods

Harvard Sociologist Robert Sampson says the key to understanding a neighborhood’s health is found in what he calls “collective efficacy.” Essentially, this term refers to the trust among neighbors. Collective efficacy can be measured in several different ways.

Would neighbors take action if a neighborhood kid were seen skipping school? Would they stop a fight on the street?

One interesting way to gauge this is by using “the dropped envelope test.” Sampson and his associates dropped postmarked-mail in the streets of various neighborhoods. The letters were returned in the range of zero – 82 percent, depending on the neighborhood.

The factors predicting whether or not someone would carry the lost piece of mail to a mailbox didn’t depend upon race or economy, but upon neighborly strength. This dramatically important for all sorts of reasons. As Sampson’s team put it:

“Collective efficacy is relatively stable over time and it predicts variations in future crime rates, after adjusting for things such as concentrated poverty, racial composition, and traditional forms of neighbor networks (e.g., friendship/ kinship ties). Dense friendship ties may facilitate collective efficacy, but they are not sufficient. Perhaps more importantly, highly efficacious communities do better on a lot of other things, including birth weight, rates of teen pregnancy, and infant mortality, suggesting a link to overall health and well-being.”

In short, if we care about the well-being of our neighbor, we have to care about our neighbor-hoods. If we want to relax the demand and pressure on the police, we have to shift the weight of responsibility from their shoulders to those of civil society.

In short, if we care about the well-being of our neighbor, we have to care about our neighbor-hoods. If we want to relax the demand and pressure on the police, we have to shift the weight of responsibility from their shoulders to those of civil society.

The Solution: Civil Society

In his book The Vanishing Neighbor, Marc Dunkelman tackles the issue of neighborliness from a different angle. Instead of “neighborhoods” he refers to “middle rings” of social life.

“Inner rings” of social engagement mostly include immediate family—your husband, wife, siblings, kids, parents, etc.

“Outer rings,” on the other hand, refer to relationships with people you don’t live near or who you might not even know – your status as a citizen, membership in a political party, an affinity group or fandom you’re a part of, your professional network, etc.

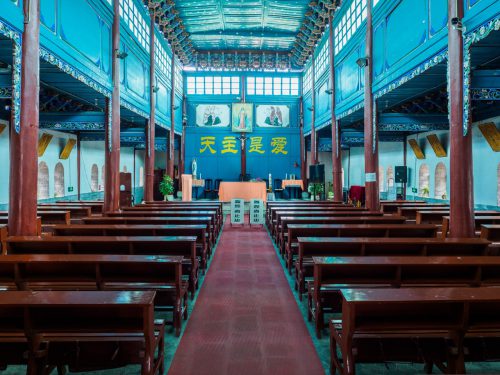

“Middle rings,” however, are usually formal or informal voluntary institutions that help shape your daily life – groups like the Lions Club, churches, carpools, or homeowners’ associations, for example.

Today, much is made out of the collapse of the nuclear family (the inner ring), but Dunkelman points to data that paints a more complicated picture. Indeed, even before the lockdown, parents were actually spending more time with their kids now than twenty or thirty years ago, not less.

For example, while 50 percent of parents had weekly conversation with their children in 1986, today some 67 percent of mothers report having daily contact with their adult children. Even as many of us spend more time interacting with our inner rings, social media naturally pulls us toward our outer rings, connecting us with, say, fellow sports fans from across the country.

The upshot of the problem is this: If we are spending more time with our immediate families (inner rings) and committing more of our identity or our sense of self to looser, larger affinity groups (outer rings), that’s likely to mean we’re investing less of our time and energy into our townships, our neighborhoods, our “middle rings.”

Conclusion

All of the above explains why police are wearing so many ill-fitting hats. We are tacitly asking them to take the roles which should be ours as we withdraw into our inner and outer circles, away from our neighbors.

The call of the hour is to reinvest in our local community. To make our streets a wholesome, welcoming place for people of every race and religion. If we want the police to have less interactions with our community, we have to take it upon ourselves to do the hard, slow work of relationship building.

Said differently, before we can defund the police, we have to befriend our neighbors. The problems of the hour are large, but the solutions are small.

Dustin Messer is Worldview Director at Christian Academy in Frisco, TX and Curate at All Saints Church in Downtown Dallas. You can follow him on Facebook and Twitter.