From the Colson Center audience:

I was disturbed by John Stonestreet’s comments on the June 3 broadcast regarding America’s original sin. The Constitution was written to withstand the civil war they all knew was coming over slavery. Did not the nation acknowledge the evil of slavery to the point of having a civil war? Was not the death of 600000 men during the war sufficient absolution for the sin of slavery? If not, then is there no allowance for forgiveness? Aren’t the writings of Lincoln and the thinking he presented to the nation sufficient enlightenment about the need to repent and value all men before God? The founding fathers inherited the problem and put together a system to deal with it and it was. I am proud of the governmental system they built, and I challenge anyone on earth to come up with a better one. If I am wrong about what I have stated above, please enlighten me

The Colson Center responds:

Thank you for reaching out on this.

I see where you’re coming from, but I think we are still on solid ground referring to slavery, not to mention the treatment of the Indians, as America’s original sin and has having an enduring legacy beyond 1865.

If I may make an analogy, if I strike you across the face with a stick, you may forgive me, but that doesn’t make the pain in your mouth go away. Nor does it mean that you won’t need some help as a result. Forgiveness does a lot, but it doesn’t eliminate all side-effects. People are responsible for their own choices in the present, but those choices are often affected by those of the past.

One of the ways slavery’s legacy endured was its impact on the African American family. Several people complained when we noted this recently, so I think some elaboration is in order. These readers pointed to the strong bonds that existed in such communities before the rise of the Great Society and its unfortunate encouragement of single-parent homes. That may be true about the 20th century, but let’s examine some aspects of the 19th.

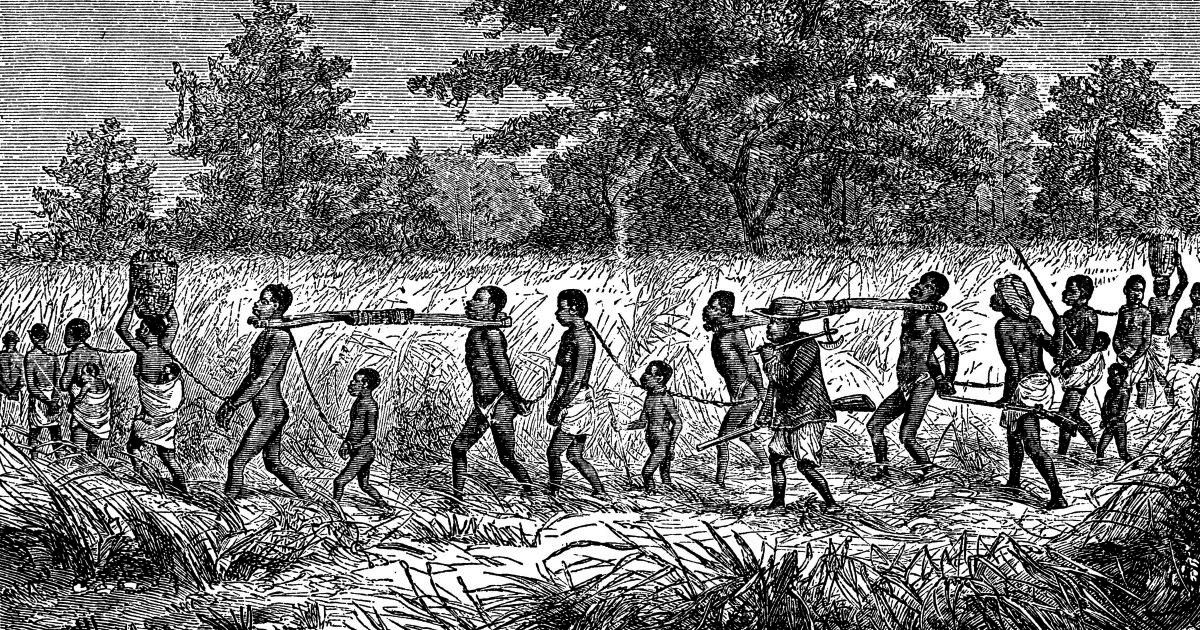

American slavery was rooted in manstealing, the kidnapping of people for the purpose of enslavement. (Please note that this was a capital offense in the Bible, both for the kidnapper and for anyone found in possession of such a stolen soul.) This in itself broke up familial relationships as people were ripped from their homes and carted across the sea in the most inhumane conditions imaginable.

Then, upon arrival in the Americas, they were sold as property without regard to kinship. Once in slavery’s full embrace, husbands and wives, parents and children were separately sold “down the river.” Finally, let’s remember the rampant sexual abuse of African American women, where masters made use of their “property” without prosecution or even much of a scandal.

This cannot go on for decades without effect. The fact that African Americans managed to carve a sense of family in and after these times is remarkable. It’s a testimony to their innate human need for family as well as to the power of the gospel, which, in a remarkable act of God’s grace, they embraced despite its association with their enslavers.

You’re right about the Constitution, at least to a point. It is a remarkable document, arguably the best governmental plan put together by human hands, and certainly better than any utopian fantasy put forward by self-proclaimed revolutionaries since its time. But, as it came from human hands, it inevitably had its failings in one form or another. Even if we ignore, for the moment, the sinful nature of the Founding Fathers, their finite abilities meant that it could not handle every obstacle thrown in its path.

For instance, one reason that anti-slavery Founders accepted slavery’s preservation was because many people reasonably expected that the “peculiar institution” was going to die out as it was increasingly unprofitable. But then came Eli Whitney with his Cotton Gin and the opening of the then-West of Alabama and Mississippi, and slavery got a morbidly new lease on life. Instead of withering on the vine shortly after 1800, it continued on 80 years after the Constitution was penned.

President Lincoln was particularly keen about the implications of slavery. His words, especially in his second inaugural address, were eloquent testimony both the horrors of slavery (“the bondsman’s lash”) and to the great hope of forgiveness and reconciliation found in Providence. You may call me biased since I’m a Southerner, but I believe that had he lived, his moderate hand could have undercut much of the racial tension that developed during Reconstruction. Unable to lash out against those who’d bested them on the battlefield, many Southerners took vengeance against those closer at hand, their former slaves and now neighbors.

These effects were amplified in many ways through years of hatred and segregation. For decades before the War Between the States, African Americans had been treated as less-than by both Northerners and my fellow Dixians. For a century after the war, even as free men and women, they were denied their full rights as citizens and landowners, they were harassed often without prosecution, and they were terrorized by the KKK and other ad hoc mobs. This cannot happen for a hundred years and then us not expect there to be side-effects.

We can point with pride in our nation at the way civil rights reforms from the late 1940s through the 1960s worked to realize in fact of law what had always been our philosophical claim about human dignity for all. And, we can critically note that some of those measures intended for the relief of the poor had baleful unintended consequences, exacerbating poverty in African American communities by encouraging fatherless homes. But, neither of these means that the long years of slavery and segregation haven’t had consequences down to today. As we like to say at the Colson Center, ideas have consequences, and bad ideas have victims, and American slavery was a horrific idea.

There are those among the advocates of critical race theory such as the 1619 Project and similar collectivist philosophies who greatly err when they write and speak and agitate. They treat African Americans as the passive victims of white power, completely unable to do anything without the aid of the sovereign state. This is paternalistic nonsense, and all too often rooted in the same kind of horrific ideologies that afflicted the 20th century with tyranny. The destructive riots they are quick to facilitate do years worth of harm to the infrastructure of African American communities.

At the same time, we’d be naive if we acted as though there weren’t large-scale, long-term problems. African Americans have individual wealth rates at a fraction of their Anglo neighbors, while their incarceration rates dwarf those of whites. We may say this is a complex situation requiring complex solutions, but it’s hardly as though tens of millions of people independently made bad decisions. Something’s not right, and it won’t be fixed by either government handouts or pull-yourself-up proverbs.

There is a middle ground between those who look to the state alone to heal what ails us and those who feel it’s none of their concern. And it’s here that the truths of Christianity may shine in a confusing time. When we as Christians see others in pain, questions of justice and oppression are significant, but they aren’t primary. Anyone may love the good and the just; it is distinctly Christian to love whether or not the beloved deserves it.

Christian love isn’t only for those who deserve it. After all, where would any of us be if God acted towards us on the basis of our rights alone? The Christian is called to love his neighbor on account of the dignity of their Adamic heritage and as an incarnation of God’s love for us, not whether the person is innocent or guilty.

If we are indeed motivated by Christ’s call to love our neighbor, then we won’t worry with questions of whether it’s someone else’s fault or even whether they deserve it. We won’t wait for the state to provide its faulty aid or abdicate this love to government agencies by our votes, nor will we remain as spectators to the suffering of our fellow human beings.

If we as Christians are serious about the universal dignity of all Adam’s sons and Eve’s daughters, as well as the call to love one’s neighbor regardless of circumstance, then we won’t wait for government approval or do so for our social media audience. We will find ways as individuals and Church communities to put some skin on this love.

Conversations between individuals for the sake of shared and humble mutual understanding, dinner invitations that never find their way to Instagram posts, after-school tutoring to raise graduation rates, small business loans to minority entrepreneurs to build tax bases. None of these things need government sanction nor the adoption of collectivist ideas, but each of these can be a wonderful act of Christ’s love in us.

Editor’s Note: This is part of an ongoing series where Colson Center staff respond to questions and comments from our audience. If Christianity is true, as we say it is, then Christians should be willing and able to offer what Francis Schaeffer called “honest answers to honest questions.”

You can go here to see more questions like this one.

If there is an issue you would like to see addressed, click on the “Follow Up Question” below.

Posted questions may be edited for form or clarity but not for content.

Topics

Ask The Colson Center

Bible & Theology

Christian Love

History

Imago Dei

Loving your Neighbor

Race

Slavery

Social Media

The State