Can men and women be friends—close friends?

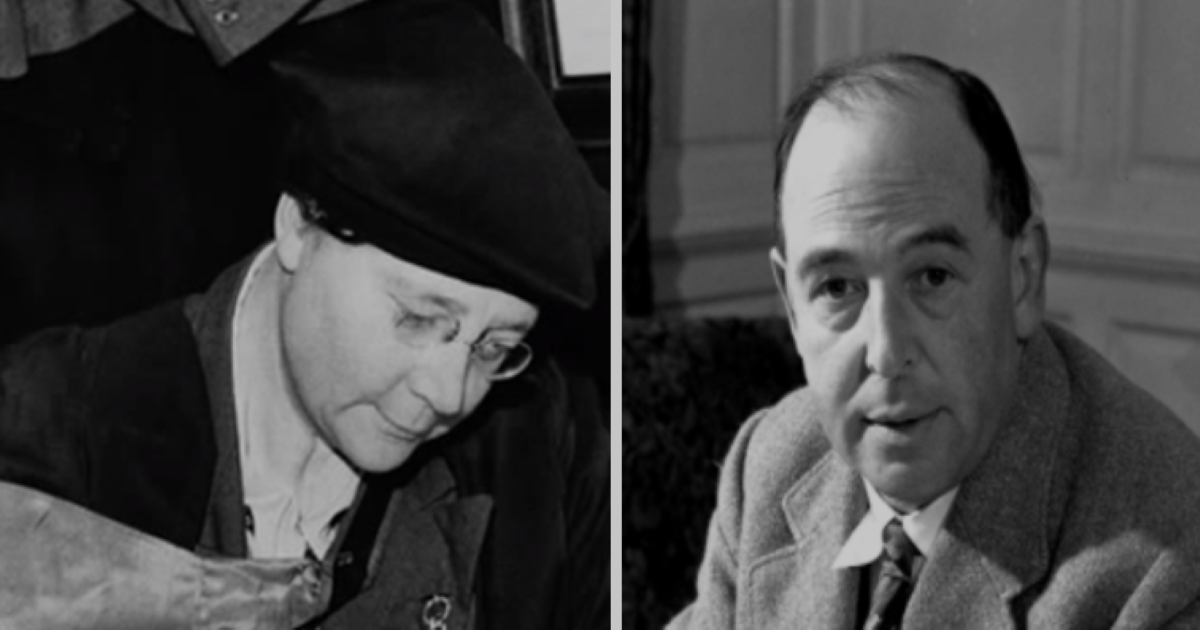

Two of my favorite people, C.S. Lewis and Dorothy L. Sayers, would have offered a robust “yes.” Their affectionate friendship endured for fifteen years, until Sayers’ death in 1957. Upon hearing the sad news, says Lewis’s stepson, Douglas Gresham, Lewis cried.

Gina Dalfonzo examines and celebrates their friendship in her lovely new book, “Dorothy and Jack: The Transforming Friendship of Dorothy L. Sayers and C.S. Lewis.” Dalfonzo chronicles their friendship from the first missive Sayers sent to Lewis in 1942: A fan letter. At that time, both were well-known writers—she for her Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries, he for The Screwtape Letters, The Problem of Pain, and his radio broadcasts about the basics of Christianity.

It is no surprise that the two became fast friends. Both were Oxford educated intellectuals, both wrote about religious and academic subjects, and both were committed Christians with a sense of humor. And yet, few people realize how strong their friendship was.

Dorothy and Jack first met in June of 1942, after Lewis invited Sayers to meet him for lunch in Oxford. Lewis was then 44; Sayers, nearly 49. Neither left a record of what was said, but the letters that followed took on “the tone of letters between friends, full of jokes, recommendations, opinions, and dialogues on subjects ranging from Virgil to Milton to Shakespeare, to T.S. Eliot,” Dalfonzo writes.

“How can a man who is neither a knave nor a fool write so like both?” Lewis asked regarding Eliot. “Well, he can’t complain that I haven’t done my best to put him right—hardly ever write a book without showing him one of his errors. And still he doesn’t mend. I call it ungrateful.”

In return, Sayers told Lewis about an annoying atheist who kept writing to her. “I do not want him. I have no use for him. I have no missionary zeal at all. God is behaving with His usual outrageous lack of scruple,” she noted irritably.

Lewis enjoyed Sayers’ accounts of the antics of her two hens, named Elinor and Marianne (after Jane Austen characters) every bit as much as he did her discussion of how difficult it was to translate Dante’s Inferno.

Theirs was, Dalfonzo writes, “a friendship that on one level caught fire quickly, as the two of them bonded over the many ideas, interests, and values they had in common, and yet took many years to deepen and intensify to the point where they were comfortable sharing their most personal struggles.”

Lewis and Sayers began sending each other copies of their work, inviting critiques. They felt no need to pretend to like one another’s efforts if they didn’t. For instance, Sayers confessed that a character in Lewis’s science fiction novel, That Hideous Strength, had begun to irritate her. For his part, Lewis said he didn’t much care for Gaudy Night, one of Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey novels.

Dalfonzo notes that Sayers likely inspired Lewis to write Miracles, by complaining that there were no modern books on the subject. Lewis so enjoyed Sayers’ “The Man Born to Be King” that he read it every Easter. They talked each other into, or out of, writing on various subjects.

Lewis—who had spent very little time with women throughout his life–grew to deeply enjoy Sayers’ company, both in person, when they were able to lunch together, or on paper. Once, after she gave a lecture on Dante at Oxford, Lewis threw her a party.

“Their unique qualities, including their different sexes—gave to the other something that made them stronger, wiser, and better,” Dalfonzo notes. Lewis grew so comfortable with Sayers that he confided to her the problems brought on by his brother Warnie’s alcoholism, and by Janie Moore, the difficult mother of a friend he had promised to look after. He also revealed to her his (then) secret marriage—something he did not even share with his great friend, J. R. R. Tolkien.

When his wife, Joy, was dying of cancer, Lewis wrote Sayers, “We have much gaiety and even some happiness . . . My heart is breaking and I was never so happy before: at any rate there is more in life than I knew about.”

Dorothy’s response to Lewis’s agonized revelations: “Believe that I do most heartily rejoice with your joys plus grieve with your griefs.”

Dalfonzo notes that today, many Christians believe there is danger in men and women becoming close friends, and recommend keeping them mostly apart, lest sexual temptation or accusations of wrong-doing result (as, sad to say, we have seen happen all too often in our “me too” era). But while Scripture tells us to be wise in our interactions with each other, Dalfonzo observes, “It doesn’t tell us to avoid each other.” She points out that some of the greatest friendships in Christendom were male-female: St. Teresa of Avila and Father Gerome Gracian, for example, or John Calvin and Renee of France, not to mention William Wilberforce and Hannah More.

Their friendships not only benefited these Christians on a personal level, but bore much fruit, both within the church and in the wider world.

Yes, Lewis does write in his book, The Four Loves, that men and women who find each other attractive should beware of allowing philia to turn into eros (if doing so would be inappropriate). However, both Lewis and Sayers valued friendship greatly and were good at it, “cultivating it assiduously and considering it just as important as other kinds of love”—which “meant that they had a proper category and role for their interactions.

“In other words, they could feel and express friendly affection without worrying that it was slipping into eros,” Dalfonzo points out. This approach to friendship with females worked well until Lewis met Joy Davidman, when intellectual friendship slowly changed to romantic love.

Dorothy and Jack’s friendship “brought out aspects of their characters that weren’t quite like the aspects brought out by any of their other relationships,” Dalfonzo writes, and Lewis’s friendship with Sayers broadened and enriched his “men only” world.

Lewis may never have changed his old-fashioned and stereotypical views of women if not for his friendship with Sayers. And Sayers may never have branched out into the world of Christian apologetics had Lewis not encouraged her to do so. Together, they provide a model for how a male/female friendship, both personal and professional, looks at its best.

Dorothy and Jack is well-researched and includes portions of many of the letters Sayers and Lewis wrote to each other. Dalfonzo also provides background for both—their youths, the development of their faith, and the cultural influences that shaped them.

Those who would more fully understand and appreciate the impact these two beloved authors had on one another should not attempt to read this book on the bus or while waiting at the doctor’s office. Instead, set aside a peaceful evening or two, brew a cup of tea, and prepare yourself for a delightful read.

Image: YouTube, Formatted